THIS IS WHAT I MEANT part 1, 1911-1965:

BORROWED OBJECTS RECEIVE PRIMITIVIST STYLE

THIS IS WHAT I MEANT part 2, 1966-1984:

NEW EXHIBITION OPENING SEPTEMBER 27 AT MUSEUM OF MODERN JEWISH MUSEUM EXAMINES « ENGINEER'S PRIMITIVISM ART »

1_Cut-up text in English, printed on paper and framed

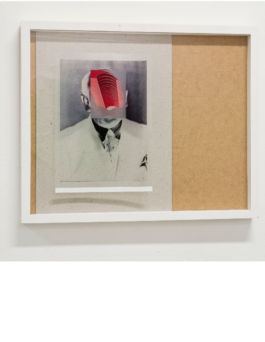

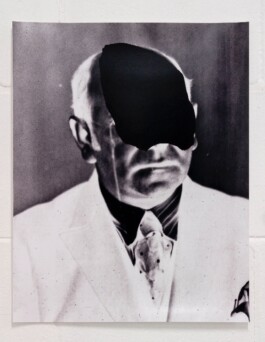

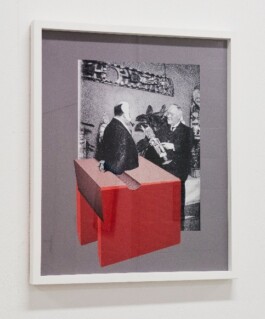

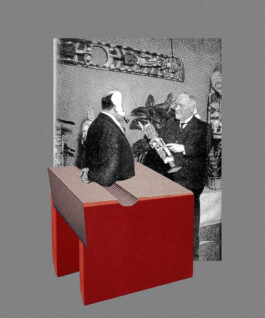

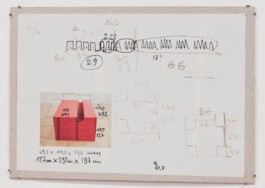

2_series of sculptural works

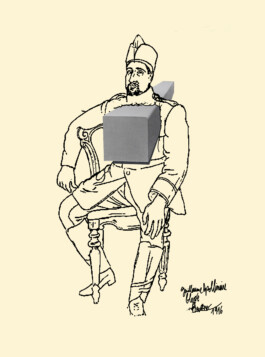

3_series of digital collages, Lambda printed on Kodak Paper 40 x 50 cm each, framed.

Exhibited at Platform Voor Aktuele Kunst Amsterdam, (P/////AKT), 2013.

part 1: 1911-1965

Part 2: 1965-1984

Exhibition views

Part 1

BORROWED OBJECTS RECEIVE PRIMITIVIST STYLE (THIS IS WHAT I MEANT part 1, 1911-1965)

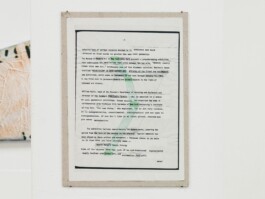

BORROWED OBJECTS RECEIVE PRIMITIVIST STYLE (This is What I Meant, part 1: 1911-1965) is a text created through using two art history articles that I have merged together, using William Burroughs writing technique of ‘Cut-up’. The first article talks about the relation between cubism and ‘primitive sculpture’ in 1911. The second article describes the appearance of early minimalist sculpture in 1965.

BORROWED OBJECTS RECEIVE PRIMITIVIST STYLE (This is What I Meant, part 1: 1911-1965), is a text written by Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yves-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, cut by Jean-Baptiste Maitre following instructions by William Burroughs.

The text is 1096 words long. Jean-Baptiste Maitre, Amsterdam, 2013

BORROWED OBJECTS RECEIVE PRIMITIVIST STYLE

«Looking back from a distance of nearly three decades at his first years as a sculptor, Robert Morris wrote in 1989 of that period in the early sixties: «At thirty I had my alienation». During 1907, the year in which the poet-critic Guillaume Apollinaire employed him as a secretary, the young rascal would regularly ask Apollinaire’s artist- and writer-friends if they would like anything from the Louvre. They assumed, of course, that he meant the Louvre Department Store. In fact, he meant the Louvre Museum, from which he had taken to stealing various items displayed in undervisited galleries.

It was on his return from one of these pilfering trips that he offered two archaic Iberian stone heads to Picasso, who had discovered this type of sculpture in 1906 in Spain and had used it for his portrait of my skilsaw, and my plywood, substituting the prismatic physiognomy of the American writer Gertrude Stein. I was out to the continuous plane that runs the forehead into the bridge of the nose; the parallel ridges that form the mouth rip out the metaphors, especially those that had to do with « up ».

Picasso was convinced that this impassive mask was as good as every other whiff of transcendence. This mood of resistance he recalls as specifically « truer » to Stein’s likeness than any faithfulness to the values of abstract expressionism. He was thus only too happy to acquire these talismanic objects; and « heads » went on to serve as the basis for a defiance that energized his whole generation. When Primitivism had been left behind in the artist’s development of Cubism, I sliced into the plywood with my skilsaw, and thus the heads had long —since I could hear— vanished from his pictorial concerns. Beneath, if not the ear-damaging whine from the back of his cupboard, a stark and refreshing « no ».

Picasso’s sudden problem was that at the end of August, THE RISE OF ANALYSIS reverberated off the four walls. The artisitic distance (to transcendence and spiritual values, heroic scale, anguished decisions, historicizing narrative, valuable artifact, intelligent structure, interesting visual experience) that separated Picasso in late 1911 from the plywood polygons —giant slabs, beams, portals— from the primitivism that Morris was to begin exhibiting in the fall of 1963 coincided with the heads that had served him earlier.

The Iberian heads and African masks had been a peculiar transformation that Donald Judd had effected in his own work during the same year. It was then that Judd’s paintings had begun to mutate into means of «distortion». Large, simplified, three-dimensional objects, such as two slabs abutted at right angles, their juncture acknowledged by an elbow of art historian Carl Einstein with a shallow through cut out of its upper face [1]. NO TO TRANSCENDENCE.

By 1966 the development of « simplistic » distortion, Einstein wrote, gave way to a period of separate act of defiance since the exhibition’s curator, Kynaston McShine, was now able to join forty more analysis and fragmentation. One among a number of attempts to give this movement a name. Finally to a period of synthesis « analysis » was also the word applied to the « primary structures ». The shattering of the surfaces of objects focused on the radical simplification of shapes and their amalgamation to the space involved, while in 1968 the museum of Modern Art employed « The art of the Real » as a rubric that would highlight the brutally.

Around them Daniel Henry Kahnweiler, Picasso’s dealer during Cubism’s development, sat down to write the most serious early account of the abandonment of any sculptural pedestal, the rubric Picasso and Georges Braque had achieved in 1911. For by that time, they had to share the real space of the viewers.

By 1968, however, « Minimalism » had come into widespread usage, edging out all other titles, such as the « Unified Perspective of Systematic Painting » Guggenheim Museum had used to emphasize the naturalistic language that would translate coffee cups and wine bottles, faces and torsos, guitar and pedestal tables into so many tiny industrialized, serialized character —only now applied to the two dimensions of painting.

To look at any work from this « analytical » phase of Cubism, is to observe several consistent characteristics. First, there is a strange contraction of the painter’s palettes, from the full color spectrum to that minimalist abstemious monochrome— all ochers and umbers like a sepia toned photograph. Picasso’s mainly erases the distinction between painting and pewter and silver. Second, there is the message of Judd’s article in the 1965 Arts Yearbook, « specific objects with a few glints of copper » the first extended attempt to theorize what was taking place (the second being Morris’s « Notes on Sculpture » of 1966). Turning to the shaped, concentrically striped canvases that Frank Stella had been making since 1961, Judd saw these as an extreme flattening of the visual space as though a roller had pressed all the volume out of the bodies, bursting its inevitable illusion of space (no matter how shallow). Space remains could flow effortlessly inside their eroded boundaries. Third, there is the visual vocabulary used to describe the physical remains of this explosive process. Slabs that begin to exists as three-dimensional objects. «Three dimensions are real space» Judd explains. «That gets rid of the problem of illusionism and of literal space, space in and around marks and colors». «This», he adds, «this, given its proclivity for the geometrical, supports the « Cubist » appellation, one of the salient and most objectionable relics of European art». It consists, on the one hand, of shallow planes set more or less parallel to the picture surface, linked to rationalistic philosophy «based on systems built before hand», but not doing this in any way consistent with a single light source. On the other, it establishes a linear network that tend to suggest that Judd thought they would best be called sculptures.

Judd, however, had the same objection to certain points, —Kahnweiler’s jacket lapels or his jawline, for instance, or the Portuguese sitter’s sleeve or the neck of his guitar. Finally, there are what Stella’s rectangular or donut or V-shaped «slabs» achieved: small grace-notes of naturalistic details, such as the single arc of Kahnweiler's mustache, a striking quality of unitariness, of simply being that object, that shape. He compared this with Duchamp’s readymades which, he said «are seen at once and not part by part».

Given the exceedingly slight information we can gain from this about either the figures or their settings, the explanations that grew up around Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubism at this time are extremely curious.

END

Part 2

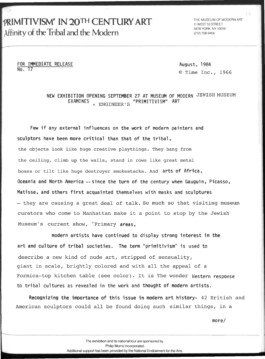

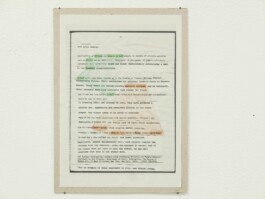

NEW EXHIBITION OPENING SEPTEMBER 27 AT MUSEUM OF MODERN JEWISH MUSEUM EXAMINES « ENGINEER'S PRIMITIVISM ART» (THIS IS WHAT I MEANT part 2 : 1966-1984)

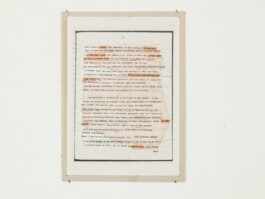

NEW EXHIBITION OPENING SEPTEMBER 27 AT MUSEUM OF MODERN JEWISH MUSEUM EXAMINES « ENGINEER'S PRIMITIVISM ART» (This is what I meant part 2, 1966-1984) is a text created by merging two existing articles that talk about ‘primitivism’ and minimal art.

The first article is from a 1966 issue of Time magazine that describes the first exhibition of minimal art at the Jewish Museum entitled ‘Primary Structures’. The second article is a 1984 press release from the MoMA New York that introduced the exhibition ‘Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern’. The text is 1019 words long. The aim is to have the ‘primary’ and the ‘primitive’ come closer.

Jean-Baptiste Maitre, Amsterdam, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

No. 17

August, 1984

Time Inc., 1966

NEW EXHIBITION OPENING SEPTEMBER 27 AT MUSEUM OF MODERN JEWISH MUSEUM EXAMINES « ENGINEER'S PRIMITIVISM ART».

Few if any external influences on the work of modern painters and sculptors have been more critical than that of tribal. The objects look like huge creative playthings. They hang from the ceiling, climb up the walls, stand in rows like great metal boxes or tilt like huge destroyer smokestacks. And arts of Africa Oceania and North America –since the turn of the century when Gauguin, Picasso, Matisse, and others first acquainted themselves with masks and sculptures– they are causing a great deal of talk. So much so that visiting museum curators who come to Manhattan make it a point to stop by the Jewish Museum's current show « Primary areas».

Modern artists have continued to display strong interest in the art and culture of tribal societies. The term "primitivism" is used to describe a new kind of nude art, stripped of sensuality, giant in scale, brightly colored and with all the appeal of a Formica-top kitchen table (see color). It is The wonder Western response to tribal cultures as revealed in the work and thought of modern artists.

Recognizing the importance of this issue in modern art history, 42 British and American sculptors could all be found doing such similar things, in a relative lack of serious research devoted to it. Admirers are hard pressed to find words to praise the new cool geometry.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York this fall presents a groundbreaking exhibition that underscores the parallelisms that exist between the two arts. "Nobody really likes this new art" confesses one of its kindest critics, Barbara Rose. William Rubin, head of the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture and director of the landmark 1980 Pablo Picasso –who is married to a maker of cool geometric paintings, Frank Stella– has organized the show in collaboration with Professor Kirk Varnedoe of New York University's Institute of Fine Arts. "For one thing," she explains, "it is not very lovable. It is uningratiating, unsentimental, unbiographical and not open to interpretation. If you don't like it at first glance, chances are you never retrospective. The exhibition includes approximately 150 modern works, covering the period from the turn of the century to the "present. Special emphasis has been placed on those artists and movements « because there is no more to it than what you have already seen: Space Warp & Optic Energy.»

Some of the objects have the look of an old-fashioned Expressionist deeply involved with tribal art, and surrealist leg pull. Carl Andre's Lever, for instance, is 100 ordinary firebricks laid on more than 200 tribal objects from Africa, Oceania and North America in a straight line. Sol Lewitt's No Title (a 6-ft.-sq. jungle gym of white painted wood) will be presented to elucidate this interest (the idea is to look through the structure, not at it). But essentially the new monumental wood figure from Nukuo announces that the engineers have now decided to make art their playground* also included is a striking, 23 foot high barkcloth and cane frame figure from pop artists recruited from the ranks of commercial and advertising artists. In addition, masks and sculptures from the personal collections of Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Derain, Nolde, Ernst,Matta, and other modern painters and sculptors will be on display.

The beginnings of "primitivism" can be traced to Paul Gauguin. It was he who just before the turn worked first with graph paper or blueprints, then handed the results over to machine shops for manufacture.

The century began melding the perceptual realism of Impressionism with flat results, finishes that are impersonal, materials that are industrial: decorative effects and stylized forms found in many non western art, including sculptures from Cambodia, Java and Polynesia, Formica and plastic, steel, chrome-plate, baked enamel, fluorescent lights. One of the artists shift away from the purely perceptual to study naval architecture, another engineering. Their lingo is strictly post-Einstein; this style gathered momentum in the first decades of the 20th century, fueled at least in part by the ever increasing speak of their art in terms of space warp time lines.

Availability of African and Oceanic tribal objects in centers of artistic activity such as Paris, and by modernists' "discovery'" of the beauty of objects previously considered mere curiosities bland and bleak -Historically acknowledge a debt to the Russian constructivists.

Tribal works soon began showing up in the studios of Picasso, Matisse, Vlaminck, Buckminster Fuller. Their enthusiasm for painters tends to focus on Barnett Newman, whose works are uncompromising vertical stripes, and Ad Reinhardt, whose severely dark-hued abstracts look almost jet black. And it was not long before tribal forms –often much metamorphosed and extrapolated– could be seen in their work. In creating their own academy of cool, they have produced a spartan art, aggressive and sometimes playful in its stark shapes. The viewer seems to be asked to overcome Many of the key works associated with seminal modernists –picasso’s Demoiselles d'Avignon and the chilly look of their bleak morphology, and his Cubist metal Guitar with cloying pastel colorism, Brancusi's Madame L.R, Klee’s Mask of fear, Nolde’s masks, Ernst's bird-Head, to name but a few– reflect the direct and inert gigantism.

Impersonal, almost deliberately dull, such objects require the maximum from the observer, offer the minimum in return. And if the viewer does not care to make the effort, he can well conclude that less is not always more.

For further information, contact Luisa Kreisberg, Director, or Pamela Sweeney, Assistant to the Director, Department of Public Information, The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York. lOO19 • • • • (2l2} 708-9750.

*For an example of other engineers at play, see MODERN LIVING.

END