SHAPED CINEMA

Exhibitions at:

Rijksakademie, 2010; Martin van Zomeren gallery 2011; Liste 16 art fair, Basel; Salon de Montrouge, Paris, 2011; LiveInYourHead, HEAD curatorial institute, Geneva, 2011; Institut National D'histoire de l'art, Paris, 2011; La Salle de Bain Art center, Lyon, 2012; Centre Pompidou, 2013 ; Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, 2013.

Video: Shaped Cinema, HD, 13', Silent, Color

Shaped Cinema is a video that brings Frank Stella’s Shaped Canvases to life, setting them in motion alongside the critical analysis of William Rubin from 1970. The editing process mirrors the logic of the paintings themselves—just as Stella’s canvases are shaped by their content, the video is structured by the visual dynamics of his work.

This project exists as a video, five photographic prints, and an artist’s book. Created in 2010–2011 at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, the artist’s book was later published by the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht.

About Shaped Cinema, as read in the catalogue of Allen&Overy Collection: "Here, the Frenchman Maitre works as a Deconstructivist, a term coined by Maitre’s fellow countryman and philosopher Jacques Derrida. The paintings of the most progressive geometric shaped canvas artist of his time, Frank Stella, are “deconstructed” into strips and then rebuilt into a new work of art."

This work has been acquired by:

StedelijkMuseum (Ann Goldstein, artistic director 2010–2013), Amsterdam

collection Allen & Overy Netherlands Partners

andaz-Hyatt video collection

Private collections (NL, BL)

Photographic Prints, Lambda prints on Kodak Paper, 50 x 60 cm, and artist book published by Jan van Eyck Ac.

Book: Shaped Cinema

edition by Jan van Eyck Academie, Language: English, Edition of 500 copies

ISBN 9072076486

buy here: https://www.pakt.nu/publication/shaped-cinema/

Shaped Cinema – Jean-Baptiste Maitre

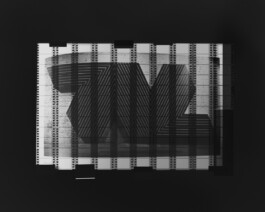

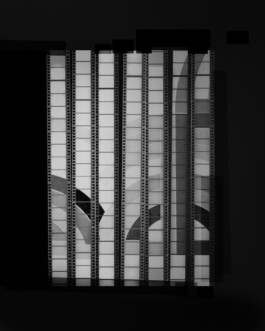

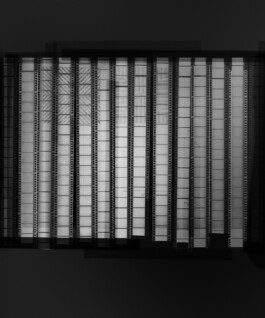

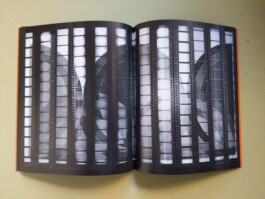

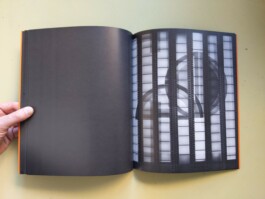

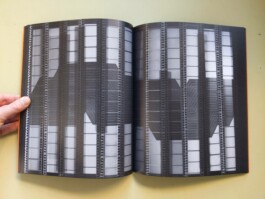

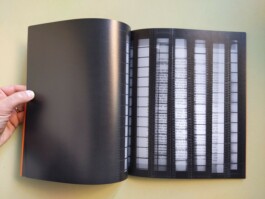

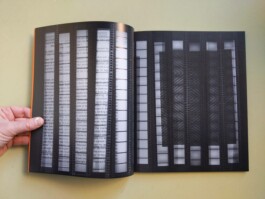

Shaped Cinema is based on the transfer of Frank Stella’s Shaped Canvases onto 35 mm motion film. Various sections of his catalogue published in 1970 by MoMA showing Stella’s shaped canvases and a critical text by William Rubin have been scanned and re-shaped to appear as 35 mm contact prints.

The resulting video is structured through using the same methodology: each illustration and text of the catalogue is divided into vertical 35 mm strips. Each film strip starting from the one on the far left is attached to the next one to follow. This finally results in the creation of a 14-minute video. The book Shaped Cinema is the visual template used to produce this video.

Specifications

2012 – English – 62 pp. – 23 x 28 cm – softcover – b/w, Edition: 500, Author: Jean-Baptiste Maître, Production and lithography: Jo Frenken, Printing: Drukkerij Walters, Maastricht, NL

Published by Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht, NL

ISBN: 978-90-72076-48-9

Video Review, in french, at the occasion of the presentation of the video SHAPED CINEMA in the exhibition BOOK MACHINE at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Comment filmer un livre, Patrick Javault, 2013 (extrait. "Shaped Cinema", Jean-Baptiste Maitre) SHAPED CINEMA https://vimeo.com/18989804 Date d'enregistrement : 12/03/2013 Date de publication : 13/03/2013 Durée : 5:30 Catégorie : Art Lieu : Centre national d'art et de culture Georges-Pompidou

Press Articles and reviews

Article 1: (English)

Catalogue extract, collection Allen & Overy Netherlands Partners

“Come in you’re welcome”, edition of 1000, 2022.

Online version of the catalogue :

https://comeinyourewelcome.nl/artists/jean-baptiste-maitre//#shaped-cinema

Jean-Baptiste Maitre (1978)

Shaped Cinema

2010

HD Film, 13’

Inspired by the art-historical term shaped canvas, Jean-Baptiste Maitre created a series of works of art (an artist book, photos and a video) in 2010, under the title Shaped Cinema.

The basic concept that a canvas or panel is rectangular, square or, in rare instances, round, was denied and contested by a group of painters who would become known as the shaped canvas artists. From the 1930s onwards, artists experimented with forms that deviated from these traditional basic forms as an expression of artistic freedom, of non-conformism, or, for example, to give the painted composition more three-dimensionality by adjusting the contours of the canvas. The shaped canvas took off in the 1960s with artists such as Richard Tuttle, Elsworth Kelly and Frank Stella. They wanted to be free of “behind-the-frame-illusionism”. In other words, they aimed to get rid of the mysticism that is supposedly contained in the rectangular paintings by Rothko, Pollock and other so-called Abstract Expressionists. They contested the idea that spiritual and intellectual paintings required set frameworks. The new generation of artists was looking for their own form of freedom, or in their own words, a new representation of truth. It brought about works that border on pictorial and sculptural art.

Maitre’s starting point for his film Shaped Cinema is a 1970s catalogue from the New York Museum of Modern Art. From the catalogue, he scans and copies paintings by Frank Stella as well as write-ups about them. He then cuts them digitally and edits them as you would with 35mm film rolls, including the perforations, next to each other. We now see the Stella catalogue reappear in photos, but fragmented and larger. Here, the Frenchman Maitre works as a Deconstructivist, a term coined by Maitre’s fellow countryman and philosopher Jacques Derrida. The paintings of the most progressive geometric shaped canvas artist of his time, Frank Stella, are “deconstructed” into strips and then rebuilt into a new work of art.

For the film Shaped Cinema, Maitre continues down this path: he digitally assembles the contact prints of the aforementioned photos into film. The urge for innovation and originality of the shaped canvas artists resonates with Maitre and, like his predecessors, he puts it into practice. But where shaped canvas artists add a visible third dimension, and thus sculpturally, to a traditionally flat and rectangular painting, he adds the factor of time by turning it into a moving image. Oddly enough, the film evokes an overall feeling of the 1960s and 1970s, partly due to the fragmentary, flickering effects. It is a digital film, made with the PC, but with an unmistakably nostalgic, analogue appearance.

It is a period that resonates with Maitre, which is also evident in another piece by him in the Allen & Overy collection: the ceramic work titled Not Necessarily Words, in which he again refers to the (neon) artists of the 1960s and 1970s. Here, too, he strips neon of all its original properties and builds up to something new that clearly refers to, but isn’t, neon. His deconstructivist approach gains Maitre new insights and new art.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Article 2 (English)

Art Forum, 2010, by Giorgio Verzotti.

Link to original article

https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201107/jean-baptiste-maitre-28907

Jean-Baptiste Maitre at Martin van Zomeren

A young French artist based in Amsterdam, Jean-Baptiste Maitre is engaged in a project that might be described as the deconstruction of the modernist text. Not Necessarily Words, 2010, the work that gives his solo show its title, appeared, at first glance, to be a piece of writing in yellow neon, inexplicably turned off; then one realized that it was a skillfully molded ceramic bas-relief. The artist told me that his intention is to compare the manual nature of a traditional artistic process with the industrial techniques that were introduced into art by avant-garde practices in the 1970s.

Another work, Plywood as Media, 2008, is composed of several planks resting against the wall—or at least so it seems. Here too, however, there is a mimetic play with materials, in this case slabs of plaster on which the artist has silk-screened an image that suggests the texture of plywood. What you see, in these works, is never what you get; Maitre overturns the very presuppositions on which his art appears to be based, and he inserts himself, as it were, into a genealogy—albeit one that he simultaneously critiques.

Maitre’s interest in art of the past pushes him to outright citation, and yet he avails himself of it obliquely, in order to reveal that the object of his interest, more than works, artists, or movements, is instead the ways in which artistic production is contextualized by the media that present, comment on, and disseminate it. His subject, that is to say, is less the ontological status of the work of art than the ideological system that creates and legitimizes it. Maitre does this, as noted above, with deconstructive intentions. One telling example is the film Shaped Cinema, 2010, whose subject is a Frank Stella catalogue published in 1970 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In a consciously old-fashioned installation, the film is shown on the wall, using a small movie projector. One needed a bit of time to grasp something familiar in the visual bombardment of shapes, colors, and words—to see typical details of Stella’s works, and to understand that these were pages from an art catalogue, the text of which was rendered illegible by the fragmentation and velocity of the film’s editing.

Working from these same images, Maitre made a series of contact prints, “Shaped Cinema,” 2010. In their deliberately unassuming black-and-white format, these pictures annihilate the chromatic richness that is fundamental to Stella’s poetics. Perhaps there is nothing more emblematic than a MoMA retrospective catalogue for concisely expressing the rationalizing, organizing, systematizing, and, if you like, normalizing function of official art history. Maitre has introduced emotional and creative disorder into the catalogue’s rational and—perhaps more to the point—institutional order, working on the effects of a historical memory full of spaces and gaps, as ours is ever more dramatically becoming.

—Giorgio Verzotti

Translated from Italian by Marguerite Shore.

Article 3 (french)

Salon de Montrouge, exhibition catalogue

« Jean-Baptiste Maitre : SHAPED CINEMA »

par Clara Schulmann, Mars 2011

“Glaser: Are you implying that you are trying to destroy painting? Stella: It’s just that you can’t go back. It’s not a question of destroying anything. If something’s used up, something’s done, something’s over with, what’s the point of getting involved with it?” 1 .

Des modèles morts, soi-disant enterrés, on continuera de discuter. Frank Stella a-t-il réellement mis fin à la peinture ? Ou plutôt relancé l’éternelle possibilité du discours sur et à partir de la peinture ? Comment les images survivent-elles à l’ère minimale et conceptuelle qui, dans les années 1960, consacre la peinture et l’image comme objets ?

Jean-Baptiste Maitre discute de cet héritage et croit à un médium visible, affirmé, quitte à produire, avec lui, le désordre. S’il a longtemps travaillé pour la publicité, c’est pour y apprendre l’art de produire des images à partir de rien. Cette artificialité, dont l’ordinateur demeure le grand metteur en scène, l’artiste la met au service du vocabulaire minimal et conceptuel- plus simple, plus économique. Une partie de son travail artistique consiste à générer artificiellement des images d’œuvres, jouant ainsi avec notre mémoire. Les œuvres minimalistes constituent notre culture visuelle : sans les avoir nécessairement vues exposées, notre mémoire en a documenté la forme. C’est cette mémoire documentaire que l’artiste met au travail. Entre nous et les œuvres, une vaste production médiatique fait écran. Jean-Baptiste Maitre choisit de donner toute son importance à cet espace « entre », réceptacle d’informations et de formes.

Comme les artistes minimalistes, Jean-Baptiste Maitre fait de son atelier la scène idéale sur laquelle rejouer les souvenirs des œuvres. Que l’atelier ressemble au white cube lui convient : pour son œuvre Bonnefantenmuseum Sculptures Report (2008) il installe sa caméra au milieu de quatre murs du musée de Maastricht et filme en un long mouvement circulaire une série de formes minimales. Les jeux d’ombre et de lumière, les vitesses changeantes des mouvements de caméra font de cet espace et de ces formes pauvres un théâtre primitif. Au minimalisme est ainsi rendu un hommage à la fois absurde (de brèves et fantomales apparitions de l’artiste lui-même dans le champ commentent un mouvement sans finalité) et expert (le film renseigne l’exposition des œuvres minimalistes dans le white cube). En réplique à une œuvre de Dan Flavin, Jean- Baptiste Maître réalise des néons en céramique (Dan Around, 2010), lourds et fragiles, à l’opposé du médium original. Là encore, et avec humour, il s’agit de fabriquer une image à partir d’un souvenir.

Avec Shaped Cinema (2010), l’artiste fait converger toutes ses recherches. Son point de départ : une forme dessinée par le passage du soleil dans son atelier. Il y reconnait un Shaped Canvas de Frank Stella. Comment matérialiser cette forme qui s’impose à lui ? En photographiant le catalogue de la première exposition rétrospective de Stella en 1970 au Moma, et en réimprimant le négatif de ces photos sur une pellicule 35mm, il obtient ce qu’il recherche : les œuvres et ce fameux attirail critique de réception de l’art (textes, légendes d’images, etc.) qui, par le commentaire, l’enserre et l’accompagne. Les œuvres de Stella ne sont plus dissociables du discours que l’on a produit sur elles, de la façon dont elles furent mises en page, des noms d’artistes ou de critiques qui leur furent associés. Fragmentaire (le déroulé de la pellicule, vertical, ne rend aucune image intégralement), Shaped Cinema devient le cartel mobile et mouvant non seulement du travail de Stella, mais aussi de la façon dont nous composons quotidiennement avec ces images. Shaped Cinema ouvre une voie : son feuilletage filmique esquisse la possibilité, comme on lit un livre, de lire un film.

Clara Schulmann

“Bruce Glaser: Questions to Stella and Judd”, in Minimal Art: a critical anthology, éd. Gregory Battcock, 1968, University of California Press, p.157.